We left off with the statement that REFORGER (REturn FORces to GERmany), the annual exercise to move American troops from the Continental United States (CONUS) to meet up with their vehicles prepositioned in Belgium, the Netherlands and West Germany and the codename for the operation to reinforce NATO forces in Europe after Soviet shells would begin falling upon the Fulda Gap would present the Soviet Politburo with a dangerous conundrum.

If Soviet forces could quickly and decisively seize control of the air over the North Atlantic (in the first week of the conflict when the bulk of the troops would be flown by CRAF to Europe), which they would have to do in the face of determined opposition from Lajes AB in the Azores, NAS Keflavik on Iceland, Thule AB on Greenland, a myriad of Norwegian NATO air bases and RAF bases in the UK, not to mention the the Royal Navy’s and U.S. Navy’s aircraft and SAMs; the Soviet Air Force and Navy would then have to shoot down civilian airliners over international waters in international airspace (assuming the airliners wouldn’t already be flying well south of the Soviet engagement area in the GIUK Gap). CRAF (civil reserve air fleet) airliners are indistinguishable from American, Delta and United Airlines; these airlines are part of CRAF and their planes operate under the same callsigns and liveries regardless if flying their own paying passengers or are under MAC (now AMC) control. Isn’t this one circumstance where Sun Tzu advises to attack not?

Maskirovka or PsyOp?

Maskirovka is a Russian term for military deception operations while PsyOp stands for Psychological Operations in the West. Maskirovka was used extensively by the Red Army during the Second World War and is a central element in Tom Clancy’s 1986 novel Red Storm Rising where NATO and Warsaw Pact forces fight a full-scale conventional clash in the Atlantic and Germany. REFORGER took on elements of both maskirovka and Western PsyOps, fooling both Clancy 33 years ago and Drachinifel yesterday, in September 2019.

Most of today’s understanding concerning a 1980s naval war between NATO and the Soviets (the prospect of other Warsaw Pact naval forces operating with the Northern Fleet were near-nonexistent) seems to be shaped by Red Storm Rising. In his novel, Tom Clancy starts off with a Soviet maskirovka allowing their air and paratrooper forces to seize control of Keflavik and the entire island of Iceland, cutting the SOSUS hydrophone network to let Soviet submarines proceed undetected and unmolested into the Atlantic, while Soviet aircraft and antiship missiles threaten the GIUK gap and sunder several REFORGER convoys and the USS Nimitz supercarrier battle group (CVBG).

We will address NATO fleet maneuvers in an Atlantic war later, including CVBG operations, but first we need to look at the oddity that is the REFORGER convoys themselves. What are they carrying? Troops? No, those are on CRAF airliners. Their equipment? No, III, V, VII Corps (the forces earmarked for REFORGER) had all their equipment and gear prepositioned at POMCUS Depots in Belgium, the Netherlands, and West Germany. New APCs? Artillery? Tanks? Doubtful:

The Lockheed Martin C-5 Galaxy / C-5M Super Galaxy is a long-range, air refuelable, strategic military transport aircraft used by the U.S. Air Force. It is the largest aircraft in the U.S. armed forces’ inventory. Using the front and rear cargo openings, the C-5 Galaxy can be loaded and offloaded at the same time. Both nose and rear doors open the full width and height of the cargo compartment.

The C-5 Galaxy routinely carries 73 troops and 36 standard 463L pallets. The aircraft is able to carry two M1 Abrams main battle tanks, or one Abrams tank plus two M2/M3 Bradley fighting vehicles, or six AH-64 Apache/Apache Longbow attack helicopters. Also, the C-5 is able to carry as many as 15 HMMWV (humvees).

As the 50-year old C-5 is in the process of retirement, video of tank-handling is difficult to find, but the 285,000-lb maximum load of the Galaxy is over 50 tons greater than the much smaller (but newer and more numerous) C-17. The C-17 can transport an entire battle-loaded M1A2 main-battle-tank (MBT), but the size differential makes the C-5M capable of transporting two MBTs today. Armor is among the heaviest vehicles used by ground forces, and the M1 MBT has been manufactured in Lima, Ohio since 1980 and was also built in Detroit from 1982-96. The U.S. Army could ship their tanks over land to an East Coast port and then by steamer to battlefields in Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark or West Germany (which they had no choice but to do before the 1970 introduction of the Galaxy, because tanks wouldn’t fit on USAF transports) however this takes weeks, most likely months.

As U.S. tends to manufacture its military vehicles with the exception of oceangoing ships far from the ocean, once MAC developed the ability to transport the U.S. Army’s heaviest vehicles with the C-5, airlift became the preferred method to transport tanks during REFORGER:

At the start of Reforger, troops of the “Big Red One,” the U.S. Army’s First Infantry Division, stationed at Fort Riley, Kan., along with other units from North Carolina and Texas, were airlifted to Europe in Air Force planes, To augment equipment already prepositioned in Europe, the First Infantry Division’s trucks and other rolling equipment came by sealift in a convoy made up of two roll-on/roll-off ships (ro/ros). These are seagoing garages for land vehicles, including tanks and other tracked vehicles, which are loaded and unloaded directly onto piers. The Big Red One’s tanks already were in position in Germany at the start of Reforger; others were airlifted by the Air Force.

There is another, more critical component to modern warfare that made airlift essential. Ammunition expenditures had risen so precipitously during the modern era that airlift has become indispensable since 1973. That year the USAF proved that a continuous airlift providing armor, aircraft, artillery, APCs and especially ammunition in hours, not sealift in days or weeks, is crucial to conduct modern war:

A quarter of a century ago, in summer and fall 1973, the Mideast seethed with tensions. Six years earlier, in June 1967, Israeli forces conquered vast swaths of land controlled by Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Cairo and Damascus failed over the years to persuade or force Israel to relinquish its grip on the land and, by 1973, the stalemate had become intolerable. Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Syria’s Hafez al-Assad meticulously planned their 1973 offensive, one they hoped would reverse Israeli gains of the earlier war and put an end to Arab humiliation. The war was set to begin on the holiest of Jewish religious days, Yom Kippur.

Trapped by Complacency

The Arab states had trained well and Moscow had supplied equipment on a colossal scale, including 600 advanced surface-to-air missiles, 300 MiG-21 fighters, 1,200 tanks, and hundreds of thousands of tons of consumable war materiel. On paper, the Arabs held a huge advantage in troops, tanks, artillery, and aircraft. This was offset, in Israeli minds, by the Jewish state’s superior technology, advanced mobilization capability, and interior lines of communication. Despite unmistakable signs of increasing Arab military capability, Israeli leaders remained unworried, even complacent, confident in Israel’s ability to repel any attack.

The Israeli government became unequivocally convinced of impending war just hours before the Arab nations attacked at 2:05 p.m. local time, Oct. 6. Prime Minister Golda Meir, despite her immense popularity, refused to use those precious hours to carry out a pre-emptive attack; she was concerned that the US might withhold critical aid shipments if Washington perceived Israel to be the aggressor.

On the southern front, the onslaught began with a 2,000-cannon barrage across the Suez Canal, the 1967 cease-fire line. Egyptian assault forces swept across the waterway and plunged deep into Israeli-held territory. At the same time, crack Syrian units launched a potent offensive in the Golan Heights. The Arab forces fought with efficiency and cohesion, rolling over or past shocked Israeli defenders. Arab air forces attacked Israeli airfields, radar installations, and missile sites.

Day 4 of the war found Israel’s once-confident military suffering from the effects of the bloodiest mauling of its short, remarkably successful existence. Egypt had taken the famous Bar Lev line, a series of about 30 sand, steel, and concrete bunkers strung across the Sinai to slow an attack until Israeli armor could be brought into play. Egyptian commandos ranged behind Israeli lines, causing havoc. In the north, things looked equally bad. The Syrian attack had not been halted until Oct. 10

Grievously heavy on both sides were the losses in armored vehicles and combat aircraft. Israeli airpower was hard hit by a combination of mobile SA-6 and the man-portable SA-7 air-defense missiles expertly wielded by the Arabs. The attacking forces were also plentifully supplied with radar-controlled ZSU-23-4 anti-aircraft guns. Israeli estimates of consumption of ammunition and fuel were seen to be totally inadequate. However, it was the high casualty rate that stunned Israel, shocking not only Meir but also the legendary Gen. Moshe Dayan, minister of defense.

The shock was accompanied by sheer disbelief at America’s failure to comprehend that the situation was critical. Voracious consumption of ammunition and huge losses in tanks and aircraft brought Israel to the brink of defeat, forcing the Israelis to think the formerly unthinkable as they pondered their options.

Half a world away, the United States was in a funk, unable or unwilling to act decisively. Washington was in the throes of not only post-Vietnam moralizing on Capitol Hill but also the agony of Watergate, both of which impaired the leadership of President Richard M. Nixon. Four days into the war, Washington was blindsided again by another political disaster-the forced resignation of Vice President Spiro T. Agnew.

Not surprisingly, the initial US reaction to the invasion was one of confusion and contradiction. Leaders tried to strike a balance of the traditional US support of Israel with the need to maintain a still-tenuous superpower détente with the Soviet Union and a desire to avoid a threatened Arab embargo of oil shipments to the West.

Shifting Scenarios

The many shifts in US military planning to aid Israel are well-documented, notably in Flight to Israel, Kenneth L. Patchin’s official MAC history of Operation Nickel Grass. Nixon, in response to a personal plea from Meir, had made the crucial decision Oct. 9 to re-supply Israel. However, four days would pass before the executive office could make a final decision on how the re-supply would be executed.

Initially, planners proposed that Israel be given the responsibility for carrying out the entire airlift. (Israel did use eight of its El Al commercial airliners to carry 5,500 tons of materiel from the US to Israel.) Israel attempted to elicit interest from US commercial carriers, but they refused to enlist in the effort, concerned as they were about the adverse effects Arab reaction would have upon their businesses. MAC’s inquiries with commercial carriers received the same negative response. Then, it was suggested that MAC assist the Israeli flag carrier by flying the material to Lajes, the base on the Portuguese Azores islands in the Atlantic, where it could be picked up by Israeli transports.

The US dithered in this fashion for four days. Then, on Oct. 12, Nixon personally decided that MAC would handle the entire airlift. Tel Aviv’s Lod/Ben-Gurion air complex would be the off-load point.

“Send everything that can fly,” he ordered.

USAF had been preparing right along to take on the challenge. Gen. George S. Brown, USAF Chief of Staff, telephoned Gen. Paul K. Carlton, MAC commander, to begin loading MAC aircraft with materiel but to hold them within the US pending release of a formal order sending them onward. Carlton put his commanders on alert and contacted the heads of other involved commands, including Gen. Jack J. Catton of Air Force Logistics Command. AFLC accorded the same high priority to Nickel Grass, and the results showed immediately. More than 20 sites in the United States were designated to be cargo pick-up points where the US military would assemble materiel for shipment to Israel. Equipment, some directly from war-reserve stocks, began pouring into these sites.

Less than nine hours after Nixon’s decision, MAC had C-141s and C-5s ready to depart. There would be some initial delays, and they would encounter some difficulties en route, but they would be the first of a flood of aircraft into Israel.

The complex nature of Nickel Grass required a flexible chain of command. Within MAC, 21st Air Force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Lester T. Kearney Jr., was designated as the controlling Air Force. The vice commander of 21st, Brig. Gen. Kelton M. Farris, was named MAC mission commander. The prime airlift director was Col. Edward J. Nash.

We’ll Hold Your Coat

The threat of an oil embargo frightened US allies. With a single exception, they all denied landing and overflight rights to the emergency MAC flights. The exception was Portugal, which, after hard bargaining, essentially agreed to look the other way as traffic mushroomed at Lajes Field. Daily departure flights grew from one to 40 over a few days. This was a crucial agreement for MAC, which could not have conducted the airlift the way it did without staging through Lajes.

When Nixon flashed the decision Oct. 12, top American officials instantly applied pressure for immediate results. MAC’s complex machinery sprang into action, but it took some hours to establish a steady, regulated flow of aircraft and crews. Initial flights were delayed because of high winds at Lajes, generating White House fury that supplies had not magically reached Israel.

Adm. Thomas H. Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called Carlton about this, saying, “We’ll have to get them moving, or we’ll lose our jobs.”

Carlton knew the airlift business. He knew that he had an adequate number of aircraft, crews, and required equipment. The fleet consisted of 268 C-141s and 77 C-5As, and Carlton knew that he could sustain a steady flow of three C-141s every two hours and four C-5s every four hours-indefinitely. He also knew that MAC could orchestrate the operation, establishing a rational flow of aircraft matching the cargo to be carried with off-loading equipment at the destination. In his plan, MAC would essentially become a conduit through which materiel would flow in a well-adjusted stream.

Three C-141s every two hours and four C-5s every four hours–indefinitely. The IDF was running through 105mm cannon ammunition at an unsustainable rate. The initial model of the M1 sported a 105mm gun, as did its predecessor the M60 Patton. In a Soviet-NATO war in Europe, with a massive expenditure of ammunition underway, an airlift (probably through Lajes) would be critical, not convoys moving not much faster than they had during the Second World War.

While it might seem that replenishing stocks of ammunition expended in battle would be the primary task of MAC, fortunately civilian airlines would again be of service. FedEx and UPS were (and remain to this day) part of CRAF. A Boeing 747-8F (UPS currently has 13 and will eventually operate 28) has a maximum payload of 295,800 lbs while B-747-100F/200F models (the primary type of cargo plane U.S. airlines operated had CRAF been activated for Operation REFORGER during the 1980s) had payloads that ranged from 210,200 lbs to 242,800 lbs. Tom Clancy specifically mentions a FedEx 747 making a CRAF 100-ton ammunition delivery in 2000’s The Bear and the Dragon, which is more evidence of poor research on Clancy’s part as in 1996 FedEx retired its last 747 (acquired in a merger with Flying Tigers, another CRAF carrier, in 1989). As the C-5 was the only USAF aircraft capable of carrying the M1 MBT until the C-17 entered service in 1991, it is probably safe to assume that transporting newly-produced armor, APCs and self-propelled artillery pieces to Europe would be the highest-priority mission for the veritable aluminum cloud.

Cover Story

So how did REFORGER turn into a story of Second World War-style convoys streaming across the Atlantic instead of the fact that the lifeline to Europe would have been instead a NATO airlift had war come? There was a kernel of truth, in the sense that if CRAF and MAC did not supply sufficient ammunition, food, medicine, other supplies and replacement vehicles, and NATO war stocks became as severely depleted as the IDF’s did in 1973, Military Sealift Command (MSC) would have to take up the slack. But going deeper, one must realize REFORGER from the beginning was based upon misdirection.

REFORGER began in the 1960s and was related to pulling American troops out of Europe to provide forces for LBJ’s 1968 buildup to 549,000 boots on the ground in Vietnam. Transporting tanks required sealift until the C-5 entered service in 1970, but the huge new cargo plane was desperately needed in Vietnam. CRAF dates from 1951, and under its Stage I and II auspices the vast majority of American forces that served in Vietnam were flown into and out of Southeast Asia aboard civilian chartered airliners.

But the pre-1970 sealift-focused approach had a massive flaw–the major targets in Warsaw Pact battle plans, specifically the small number of available European NATO ports:

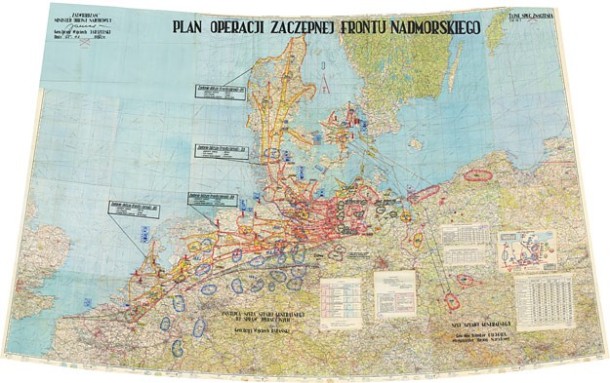

This is a plan for the end of the world, dated 1970.

The arrows are armies and the red vertical symbols are nuclear bombs, all part of a part of Cold War contingency plan crafted by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies in case of war.

War that would have destroyed civilization.

The map and other documents, discovered in Poland, show how the Warsaw Pact aimed to put tanks on the shores of the Atlantic within 14 days of the first shot being fired.

Among Warsaw Pact armies, Poland’s was second in size only to the Soviet Union’s. It had a peacetime strength of 361,000 troops and could expand to 865,000 upon mobilization. It had 15 combat divisions, versus the U.S. Army’s 10 divisions today. The Poles had 2,880 tanks, 2,750 armored personnel carriers and more than 2,000 artillery pieces.

In the event of war, the Polish and Soviet armies would have marched west, invading West Germany, Denmark, The Netherlands and Belgium. The attack was meant to overrun NATO’s northern ports on the Atlantic, preventing the arrival of reinforcements from the U.S. and Canada. Polish marines and airborne troops would invade Denmark on day five, knocking the tiny NATO country out of the war.

All of this was to be accompanied by the use of hundreds of nuclear weapons.

The Cold War, as one of our number has previously written, was in reality a NUCLEAR cold war. Reinforcing NATO by sea would have been much more difficult than simply forcing convoys through in the face of determined Soviet missile and torpedo attacks…

The Polish maps make it clear just how many nukes the Soviets would have dropped. Large-yield nuclear weapons would have wipe out economic and political targets. The West German cities of Hamburg and Hanover and the ports of Wilhemshaven and Bremerhaven all would have been nuked.

In The Netherlands, The Hague, Rotterdam, Utrecht and Amsterdam were on the nuke list. Belgium would have lost the port city of Antwerp and Brussels, the site of the main NATO headquarters.

Even tiny Denmark, with a population of just under five million at the time, would have been hit with no fewer than five nuclear weapons, including two dropped on the capital city of Copenhagen.

…and REFORGER was pretty much meaningless in the face of all-out nuclear war:

The Warsaw Pact would have used many more smaller “tactical” nukes against NATO command posts, army bases, airfields, equipment depots and missile and communications sites.

Radiation would have contaminated farmland and water supplies. Refugees fleeing the fighting would have been particularly hard hit. Radioactive fallout would have affected a far larger area than the bomb blasts themselves.

In all, Warsaw Pact plans called for 189 nuclear weapons: 177 missiles and 12 bombs ranging in yield from five kilotons—roughly a quarter the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima—to 500 kilotons.

And that was just for the Northern Front. There were two other fronts, Central and Southern, covering the rest of Germany down to the Adriatic. Atomic bombs factored into Soviet plans for those areas, too. According to the Hungarian Cold War archive, Vienna was to be destroyed with two 500-kiloton nuclear bombs, Munich one.

Escalation to all-out, global nuclear warfare would have been practically inevitable.

If this was the case, why was Exercise REFORGER conducted annually after the end of American involvement in Vietnam in 1973?

Pingback: From PSYOPS to SIOP, Part 3: Russian Reaction | In The Corner, Mumbling and Drooling